The Senegalese Cultural Exception

In December 2013, the famous Ballet Béjart performed for three days at the Dakar Grand Theatre. It was two years after the inauguration of this immense building of Chinese architecture, one of the pieces of President Abdoulaye Wade’s defunct “Seven Wonders” project, which was also to include the Museum of Black Civilizations, the School of Arts, the School of Architecture, the National Archives, the House of Music and the National Library.

That evening, I experienced a fascinating show, in front of a large and enthusiastic audience. The performance of Maurice Ravel’s Boléro was the high point of an evening in which the beautiful rubbed shoulders with the sublime.

Read the column – Mali’s « Democratic » Pause

I remember the Béjart dancers alongside those of the Jant Bi of the School of Sand company, founded by Germaine Acogny. Germaine herself was a former pupil and spiritual daughter of Maurice Béjart. I’d like to take this opportunity to remind you that Béjart was Senegalese, as the son of Gaston Berger, Senegalese and the father of foresight. Everyone was delighted to see, thanks to the dynamism of the teams at the time, this symbolic place welcome such a great company.

Last week, as is often the case, I returned to the Grand Théâtre which now bears the name of Doudou Ndiaye Rose, the man Abdoulaye Aziz Mbaye never ceased to remind us was a “living human treasure”. This time, the program announced a performance by the famous Russian ballet, the Bolshoi.

Read the column – Gaza and the Values with Variable Geometry

In truth, the results of the performances were a tad more disappointing than promised. Although a Bolshoi soloist was on hand, we were only treated to a short excerpt from Swan Lake, Tchaikovsky’s famous 19th-century fairytale ballet, which tells the story of a tragic three-way love affair between Siegfried, Odette, the white swan, and Odile, the black swan. The Russian dancer was graceful, her gestures elegant, and one could only regret the short duration of the score.

In addition to this picture, we appreciated the Senegalese genius, who always reminds us that we are in Senghor’s country and that culture is part of the social body. A little girl, clearly not yet ten, graced the audience with her sublimely beautiful piano notes. She played a score from Johann Strauss’s Tales from the Viennese Forest. Her name is Aminata Ba. She has a talent and skill that impressed and touched me. Another little boy also performed the Blue Danube, a famous Strauss waltz. There were other performances of dubious charm, but the festive spirit prevailed in a half-filled 1,800-seat hall.

Read the column – The Savana Conclave

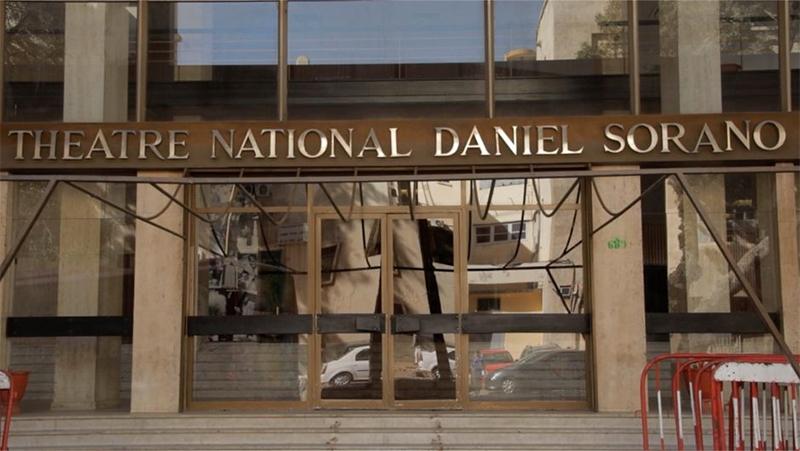

I recount my outings as one recounts one’s readings. But for me, evoking this show brings with it a certain nostalgia for a theatre whose corridors I’ve regularly walked, but never loved. I find it kitschy and dark; it lacks something of the mystique of theatres where, at night, one might encounter the ghosts of departed actors and scene directors.

A certain nostalgia, as I said, but also a singular sadness, because this theatre doesn’t play the role it should. It’s more of an auditorium, hosting concerts, public conferences, political meetings and religious events, rather than a privileged venue for the Senegalese and international performing arts. Theatre, dance, circus and opera do not have the access they deserve.

The economic model of public cultural infrastructures leaves little room for manoeuvre to the administrators who run them; and this configuration has a regrettable impact on the production and promotion of our arts and artists.

[themoneytizer id= »124208-2″]

Léopold Sédar Senghor, not being the economic ignoramus that some chagrined minds would like to paint him, built our Nation on a foundation of culture and ideas. He set up our cultural institutions as instruments for promoting our country and its art de vivre. Culture was also a powerful economic factor for a country once devoid of natural resources.

It’s spectacular to note that Africa’s biggest Biennale remains Dak’Art, while the country still has no museum of contemporary art. Like Aminata Ba, who divinely plays Strauss’s Tales from the Viennese Forest on an ordinary evening in Dakar, Senegal is a land of miracles. So far, we’ve been living – especially culturally – on the income of the poet-president. Does this absolve us from the need to do better?

By Hamidou ANNE / hamidou.anne@lequotidien.sn